Five creative lessons from Factory Records

How world-building, lore-making, and creative releasing helped make a label legendary

In 1978, music promoters Tony Wilson and Alan Erasmus started the independent record label Factory Records in Manchester, England. It wasn’t long before the label was earning a legendary reputation for releasing culturally significant albums (Unknown Pleasures by Joy Division and Power, Corruption, and Lies by New Order, among many others) and for their unique approach to what they released and how they did it.

The resulting body of work, built over decades of activity, is an instructive model for artists, metalabels, and creative groups of all kinds on how to be prolific, how to have fun, how to make a lasting cultural impact, and the power of collective worldbuilding.

Here are five creative lessons from the Factory Records catalog.

#1: Anything can be a release

One of the most notable qualities of Factory Records is the diversity and breadth of release types. While there are dozens of traditional albums and singles, there are also a wide range of less conventional releases, ranging from posters, objects, and events to ideas and concepts.

For example, Factory Records created their own nightclub, the Hacienda, as a release (FAC 51), to promote and support music from Manchester (see this 1983 video of Tony Wilson showing the BBC around the club). Sometimes a release was as simple as indexing a party with a release number. Other times a release was a piece of merchandise like a T-shirt (FAC 13T).

The approach to creating releases was so broad it included a cat that lived at the Hacienda (FAC 191), a lawsuit against the label (FAC 61), and even founder Tony Wilson’s coffin (FAC 501).

Factory’s wild catalog shows that a label or artist’s releases don’t have to stick to a particular medium or even require a defined level of production value, effort, or seriousness. Releases don't need to fit a particular format or expectation to build a larger narrative. Each release builds upon the lore of the label and furthers its cultural point of view.

#2: Catalogs are bespoke classification systems

Factory developed a unique classification system to organize all of their releases. Release numbers weren’t always chronological — some numbers were saved for special releases — and some release numbers were issued more than once, while others aren’t associated with any release at all.

Release categories were given prefixes. For example FACT was a prefix that indicated a full album, while FAC was for miscellaneous release types.

The result is a catalog sorted into a color-coded periodic table (seen above) that shows all of their releases together in one unified system.

When thinking of how to catalog your work as either a group or individual, Factory shows that we can create our own rules for how work is organized, presented, and hierarchized, revealing stories, ideas, and motivations beyond just the releases themselves.

#3: Releases can be created by a community

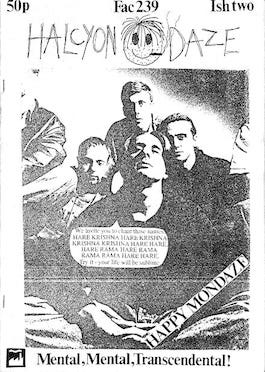

In 1990, a Factory Records collector named Jim created a fanzine titled Halcyon Daze #2 and requested for it to be categorized as an official release. Tony Wilson agreed, giving Halcyon Daze a release number (FAC 239).

Factory Records also created a release number for an album released on another record label. The album, Uncle Dysfunktional by Happy Mondays, was released on Sequel Records, not Factory. Still, Factory listed it in their catalog (FACT 500).

This approach counterintuitively demonstrates that releases may not even have to be original output. Releasing can be a form of curation, signaling the importance of a work wherever it was released and whomever made it.

#4: Releases are a form of worldbuilding

The legacy of Factory Records continues to live on in part because of the cultural impact of individual releases from groups like Joy Division, but also because of the narrative created through a holistic view of the entire catalog.

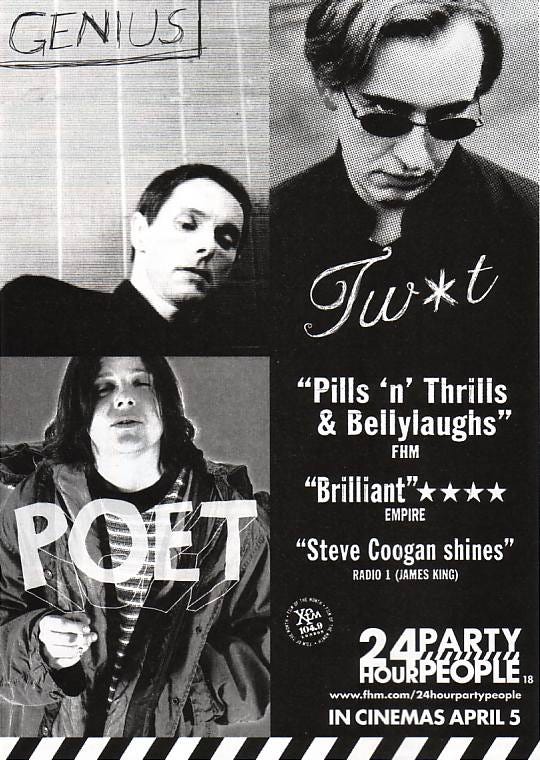

Taken altogether, the music, the venue, the show flyers, the casket, and even the lawsuit tell a larger story about the world Factory Records created. A world so vivid that a great film (24 Hour Party People) was made about it, whose theatrical run, soundtrack, and even film website were each Factory releases.

When a world becomes so rich it begins producing narrative releases about itself, that world has truly come alive.

#5: Labels can be anything we want them to be

Factory Records challenges the idea of a label itself: it’s more than a vehicle for selling music, it’s a multimedia vehicle for cultural influence.

When we were exploring the ideas that led to the creation of Metalabel, the Hacienda release by Factory Records was a key source of inspiration for how open the idea of a label really could be. Labels don’t have to stay in one lane – they can define their world and catalog however they wish, and keep building on it, release by release, over time.

The lessons of Factory are applicable to individual artists and collections of artists working together on shared cultural goals as metalabels. Factory Records underscores the power of world-building, creative releases, cataloging, and shows how creative visions can stand the test of time.

Continued Reading

The entire Factory Records website is worth a deep dive

This post on The Art & Design of Factory Records has a lot of great info

The Hacienda: How not to run a club by New Order’s Peter Hook is an excellent look into how much money was spent managing (and mismanaging) the Hacienda

This Factory Records Spotted on Metalabel.xyz looks at their work from a metalabel lens

To learn more about how to make your own label, go here to join the waitlist for Metalabel and here to learn more about how metalabels work

there is something so refreshing, and so empowering in the way you're reminding all of us that we're basically 'free' to do / create / release whatever / however we want. Yet that playbook-explosion can also be paralysing. Onwards ✌️

Brilliant as always - Thank you Metalable Multiplayers!